I am an African American woman with a brain disorder – aka mental illness (specifically manic depression, also known as bipolar disorder). I have spent time in a mental health treatment facility, will probably need medication for a lifetime, and have spent many hours in a therapist’s office. I’ve got a whole professional team that works with me to keep me sane.

I used to be ashamed and secretive of the reality described in the previous paragraph but proud of the life described in the first. Now it’s an integrated whole. I know that taking off the cape and stripping my chest of the ‘S’ doesn’t make me any less of a strong African American woman. Superhero status is not required. I cannot save the world and sometimes I’m the one that needs saving.

Like many people I once felt that having a mental illness was a sign of personal weakness. As a mental health professional I spent lots of time convincing people otherwise, but when it was my turn I felt that going to the psychiatrist was a sign of failure. I tried running, acupuncture, yoga, Chinese herbs, meditation – anything but get ‘mainstream’ medical attention. I did not want to go to a psychiatrist because,“ Nothing is wrong with me. I’m not crazy!”.

I had no issue with going to the dentist, gynecologist, or orthopedist. Like many African Americans I stigmatized mental illness in a way we do not stigmatize obesity, diabetes, hypertension and so many other chronic and life-threatening illnesses. We will take pills to lose weight or lower our blood pressure but not to get or stay mentally well.

According to the mythology that surrounds the strength of African Americans, ‘falling apart’ is just not something we do. We survived the Middle Passage, slavery, racial oppression and economic deprivation. We know how to “handle our business”, “be a man”, or “be a woman”. We see therapy as the domain of ‘weak’, neurotic people who don’t know what ‘real problems’ are. Instead, to deal with our psychic pain we eat our way into life-threatening obesity, excessively use alcohol and drugs, and act-out violently through word and deed, but we do not go crazy.

Because being ‘crazy’ means you can’t handle life and in our story of who we are, we are survivors who can handle anything,; which means we do what we have to do to survive. But this does not usually include a trip to the mental health professional of our choice. It is time to add this to our survival toolkit.

Is it really better to be a drug addict, obese with high blood pressure and diabetes, or be verbally/physically/

At some point we must stop worrying what other people are going to think and get about the business of getting well and moving forward with our lives.

So how do African Americans begin to eliminate the stigma of mental illness so that we can get the help we need sooner rather than later, and support those who need it?

1. Talk about it. Don’t whisper or gossip about it. Talk about it at the BBQ. From the pulpit. On TV. On the radio. With our doctors. With our loved ones. If we can talk about our ‘sugar’ and our ‘pressure’, then we should be willing to talk about our depression.

2. Support each other in getting help. We send friends to the doctor for the nagging back pain so send them to get relief from their mental and emotional pain too. And don’t forget to ask them how they are doing as time passes; they need friends more than you know.

3. Let us not stigmatize the brain. It is attached to the body so mental illness IS a physical illness, especially as chemical imbalances are at the root of their expression. Furthermore, the biochemical impacts of a brain disorder are felt throughout the whole body, not just in the brain.

4. Say, “This person HAS a mental illness”, NOT “This person IS mentally ill”. We do not say, “That person IS cancerous”. Words have power.

5. Acknowledge that those who survive a brain disorder are as much survivors as family and friends who survive life-threatening diseases. Understand that we work just as hard to stay sane as the addict does to stay sober. As cancer or addiction go into remission so too do brain disorders.

6. Support people who share their stories of brain disorders. It is time to show that the faces and lives of African Americans with a mental illness are not just the faces and lives of the homeless person talking to the unseen. It is my face and my life; and the faces and lives of so many other men and women like me.

7. Advocate for accessible and affordable, culturally appropriate mental health services.

“Coming out” requires courage. Like any other consciousness-raising process, a range of role models that represent a variety of experiences with mental illness will change perceptions. As a community we have lists of accomplished African Americans to inspire us in our various endeavors. We need a list of African Americans with mental illness who have survived and thrived.

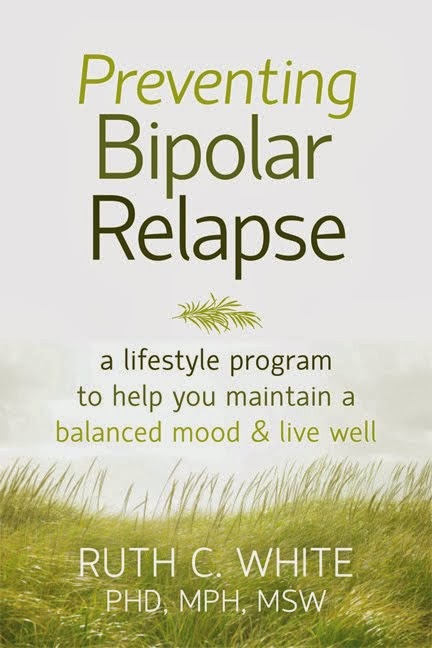

No doubt due to the stigma, it was difficult to find names of well-known African Americans with a “‘confirmed“‘ history of mental illness – and this is no place for innuendo or rumor-mongering. So I will start this list with me: My name is Ruth White and I have manic depression. I am a mother, poet, researcher, writer, kayaker, hiker, traveler, professor, swimmer, and as sane and happy a person as you would ever want to meet. My brain disorder does not define who I am.